ANOTHER ROADMAP FOR ART EDUCATION – Barcelona, Spain – August 2012

Javier Rodrigo, Aida Sánchez de Serdio, Judit Vidiella, Carla Padró

-

Policies and practices of arts education in the context of the increased interest in the role of creativity (creative turn), and their relation to the concepts and assumptions of the UNESCO Roadmap for Art Education.

During the last month we explored cultural and educational policies in Spain (focusing especially on the autonomous communities of Cataluña, Euskadi, Andalucía y Extremadura). We paid attention to public administration in the areas of culture and education, as well as to the role of private foundations and of museums.

In this first exploration we identified discourses and practices relating to creativity in different ways: In a first definition creativity is considered the foundation for a bundle of economic activities in the arts and culture sector, as is the case in the term

cultural industries

(Cataluña). In a second meaning, creativity can be understood – following the same line, but in a broader sense – as instrumental for the development of an

entrepreneurial spirit

in a general economic sense (Extremadura). Thirdly, we found a meaning, still ambivalent and too broadly defined, which is

social innovation

(Euskadi), understood as a wide range of capacities and collective resources such as participatory culture, intelligent cities, transversal learning, entrepreneurship, new technologies etc. Finally, we identified a differential use of creativity, conventionally related to terms like expression or communication, in some private foundations or public agencies dedicated to social work with the arts. In this case, creativity is seen as an instrument for

social integration and pacification

on a personal as well as a collective level.

Depending on the context, art education relates differently to these discourses. Education in the visual arts (educación plástica y visual) in compulsory education is strongly influenced by cognitivist perspectives on learning, as well as a semiotic approach to visual language, thereby universalizing the subject, knowledge as well as artistic practice. Culture is identified with a non-problematizing and universal notion of heritage. Approaches to the pedagogical in areas like culture, on the other hand, are still anecdotic and follow fashionable terminologies (collective creativity, commons, educational turn, radical pedagogy, etc.)

Still, experiences exist that try to construct complex and reflexive relationships between cultural/artistic practice and education, which could form objects of inquiry for

Another Roadmap for Art Education

.

-

Critical assessment of the continuing hegemony of a Westernised art education

In relation to this point we propose two lines of research. Firstly, the inquiry would examine the tensions between Spain and Latin America focusing on the initiatives for cooperation and promotion of culture of Spain abroad. In this area, it is important to highlight the missing tradition of post-colonial or decolonial studies in Spain. Still, this tension can be found in the so-called Latin American Studies as well as in the relations maintained with the former Latin colonies. Here, we find a re-inscription of Latin identity from the Spanish empire, updated in the trademark “Spain”, as a non-conflictive and pacifying understanding of heritage and of the phenomenon of colonization, within the paradigms of Spanish nationalism and imperialism. By consequence, the object of the study would be the discourses of programs initiated by bodies and external agencies like the Instituto Cervantes, the AECID (1992) or the SEACEX (Sociedad Estatal de Acción Cultural en el Exterior) (1996).

These discourses move between the promotion of Spanish high culture and of the virtues of the Spanish empire on the one hand, and the practices of Spanish cultural workers (artists, and especially architects) in community or institutional frameworks with clearly aesthetic evangelist contents. This approach would require close collaboration with the countries where these propositions have been implemented, contributing from our position the analysis of diverse discourses of the expansion of Spanish culture.

Secondly, another possible working environment would be to analyze the models framing the negotiation of cultural practices and education at the crossroads and spaces of relation of migrant cultures, quite a recent phenomenon in Spain. In this case, the inquiry would focus on a series of situated practices that put the hegemonic framework of multiculturalism and peaceful coexistence of cultures in debate and conflict. The aim would be to analyze case studies of multicultural art education practices, that escape the Anglo-Saxon references and suspend the notions of culture, citizenship, artist and institution which are the fundament of art education.

-

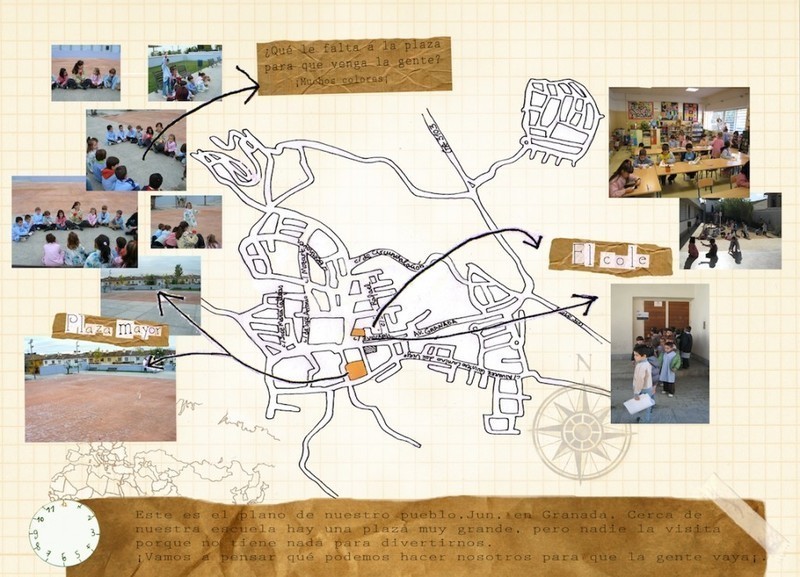

Studies and current practices which plot alternatives and develop other paradigms for practice and research in art education

In this section, we want to share our position regarding a series of problems and tensions arising in the analysis and work with the practices and initiatives of “Another Roadmap”. Firstly, we consider that our approach to different experiences should not be based on the model of best practice, but in the analysis of case studies, following different methods which allow us to work through their tensions and complexities, apart from defining them as paradigms or radical practices.

Secondly, in order to avoid excessive involvement and bias in the research we don’t consider working on our own practice, , while the method of case studies allows us to critically reconstruct experiences. Thirdly, our analysis of practices intends to establish relations between practices and the cultural, educational and social policies in which they are framed and that we have already started to study. In this sense, we aim to situate the cases in different historical lines and discourses of cultural and educational practices, gaining in this way a certain notion of critical distance.

Out of these reflections, we have developed a framework for the selection of cases, and are simultaneously thinking about the amount and the scope of cases that would allow us to study diverse practices of different type in a range of contexts, institutions and geographical areas of Spain, and at the same time to work on recovering diverse voices, agents, and knowledge implicated, always focusing on lines of tension and complexities.

QUESTIONS RELATED TO THE DIMENSIONS OF THE RESEARCH OF

ANOTHER ROADMAP FOR ART EDUCATION

a) Possible critical and reparative readings of the UNESCO documents that emerge in different contexts. Other commitments and articulations of core debates and agreements integrated into your work.

We have not been able to find any explicit reference or influence of the UNESCO Roadmap for Art Education in Spain, nonetheless we think can explore the deployment of the notions and assumptions proposed by the Roadmap in the discourses and practices of art education in Spain. In this case some possible questions would be:

- How is the Roadmap differently received when debated among diverse groups (school teachers, art educators, “radical” educators, educational theoreticians…) and why?

- How is creativity defined through both discourses and practices in art education in Spain?

- How do these definitions vary or even contradict?

- What is the “expediency” of creativity in each of these discourses and practices?

- How is social and cultural dialogue defined through both discourses and practices in art education in Spain?

- How do these definitions vary or even contradict?

- What is the “expediency” of social and cultural dialogue in each of these discourses and practices?

b) Local and global, official and unofficial histories influencing the work in various geopolitical regions, including histories not directly identified as “arts education”.

In the case of Spain the historical dimension could be considered in two different fields: that of formal education and the non-formal/experimental education. The former has been studied extensively whereas the latter needs a more systematic study in order to recover past references beyond the usual claim of Republican (pre-Franco’s Dictatorship) educational models. Here some possible questions are:

- How are contemporary non-formal/experimental theories and practices of art education related to past educational models or experiments, both explicitly or involuntarily?

- What other educational past references can be identified beyond the Republican radical educational experiments (workers self-education, anarchist schools, etc.)?

- Can past non-radical educational movements be also at the basis of contemporary radical projects?

- How does this favour a complex understanding of contemporary non-formal/experimental education projects?

c) Commitments to social/political justice and their articulation in various contexts. Social and political stakes in relationship to radical art education and other pedagogical practices.

We think that in order to explore this dimension we would need to develop some definition of social/political justice since this is a notion useful both to the public administration (under the more mild term of social participation) and to critical movements such as the Occupy movement in Spain. We believe that this definition might emerge from the very exploration of the educational practices through questions such as:

-

What relation can we identify between the different notions of social/political

justice

, social/political

critique

, social/political

participation

, or social/political

transformation

in contemporary radical arts education projects? - How do contemporary radical arts education projects negotiate the demands of the political structures (social, cultural, educational) in which they carry out their practices?

- How does this negotiation affect/resituate their discursive statements regarding their position in terms of social/political justice?

d) Practices around which arts or aesthetic devices/cultural practices/creativity manifest in these spaces, including spaces that don’t identify as “arts education”.

During our first overview search of cultural and educational policies we have found that some interesting critical projects seem to develop practices that some would not relate to “arts” or “education” at all (collective management of urban spaces, activist research, traditional crafts, etc.). This fact raises questions around the definition of the arts and of educational practice:

- How is the identification of arts education projects as such influenced by competing social definitions of what is “art” and what is “education”?

- Why and when do educational projects define themselves as “education”, “arts education”, “social work”, “political work”, etc.?

- How do they negotiate their recognition and (in)visibility through this “self-naming strategy” (provided it is conscious and deliberate) in different contexts?

- Does this shifting involve a change in the notion of creativity they assume?

- What is the range of practices they develop? Are they differentiated too in the terms above mentioned (education, arts education, etc.)?

e) Role of “the arts” at a discursive level in various settings with the above commitments. Construction of the meaning of “arts”, “artist”, “radical” or “arts educator”.

The discussion about these concepts is a key element in our view. We can identify at least two debates here: the tensions between the notion and role of artists and educators, and the definition of what is “radical”. Some of our questions are:

- What are the capacities socially attributed to artists and educators and what difference do they make in their respective roles?

- How are these differences related to their identification with (or differentiation from) radical art education projects?

- When collaborations between artists and educators take place, what are the relationships that emerge between the two roles, and with the participants?

- How is the term “radical” implicitly and explicitly defined by the educational groups that use or identify with it? Which of their practices do they consider radical and why?

- How do other groups which do not identify themselves as radical define the term? How do they differentiate their practices from the radical ones and why?

- How does the term “radical” work as a differentiating notion (that is, a term of distinction) in the contemporary “symbolic market” of art education?