This text was written by Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa in August 2012 as a starting-point for the research that the Kampala Working Group is now undertaking under the aegis of the Another Roadmap School.

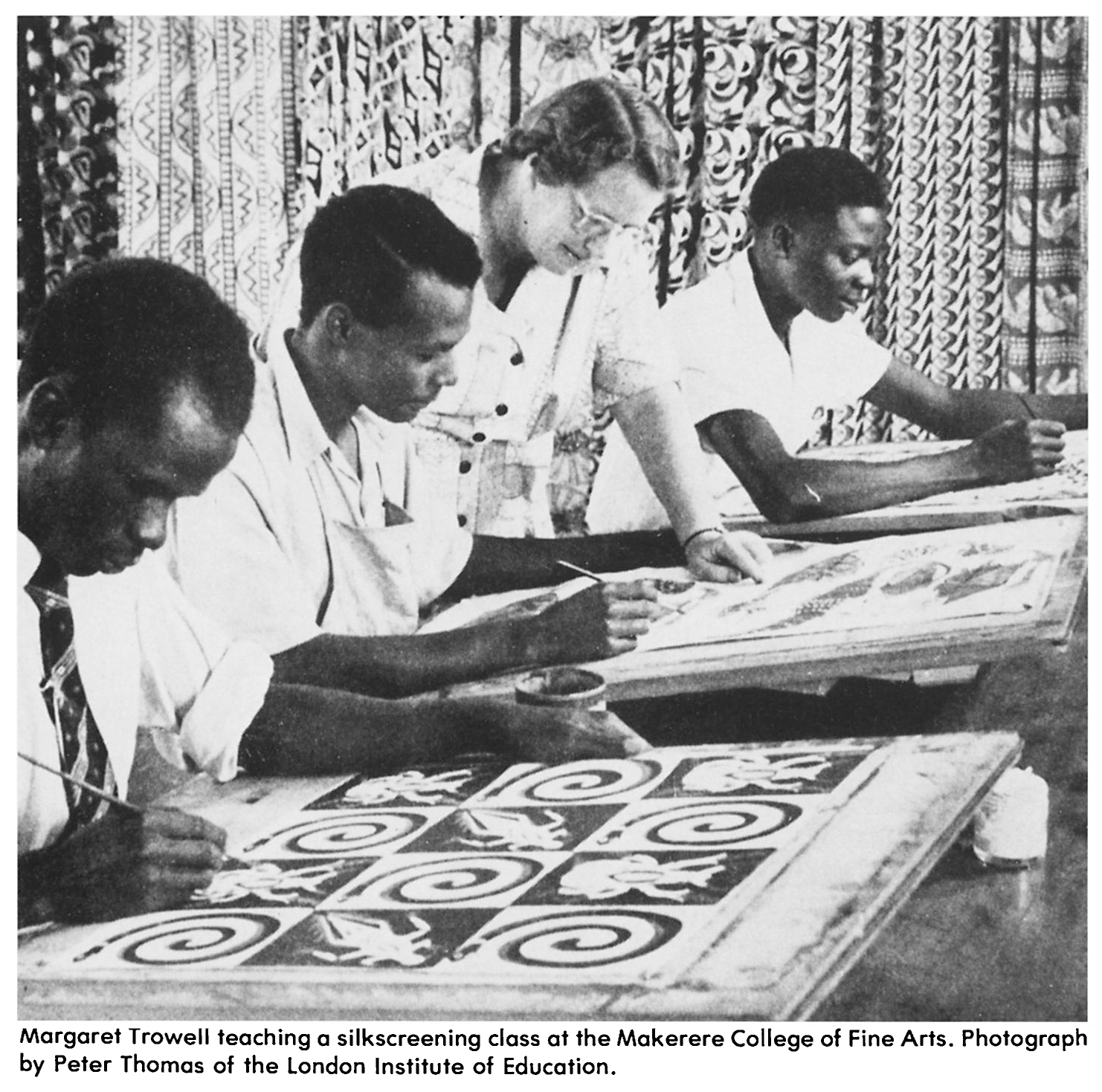

Despite extensive evidence of variety and variation in the material cultures and aesthetics traditions that evolved over centuries across the African continent in response to differing social, political, environmental and cultural conditions and exchanges, the British colonialist Margaret Trowell (1904-1985) who established ‘indigenous’ fine art discourse in British Colonial East Africa in the 1930s and 40s more or less singlehandedly, fervently believed in the existence of a pure, innately unified ‘African’ aesthetic.

She characterised this aesthetic as spiritual and expressionistic, unconcerned with formal qualities and rooted in ‘the African’s’ deep connection to his rural habitat.

1

She felt passionately that this aesthetic should be nurtured ‘in light of the African’s needs’, and shielded from the contaminating influence of Western art history, which she believed would only result in the creation of a mediocre derivative art style. The challenge that she initially faced was to identify that upon which an East African aesthetic tradition could be built.

For various reasons, the material culture of the communities of East Africa has historically been markedly different from that of their counterparts to the north, west and south. There are long-established traditions in the creation of pottery, textiles and decorative items in the region – also in the decoration of homes – but with the exception of what is known as ‘the Luzira Head’

2

, archaeologists and anthropologists arriving in this part of East Africa from the late 19th century were able to find few if any examples of figuration (i.e. sculpture, masks, pictures). This might have been because the materials from which most such objects were made were perishable and none have survived. But it is also likely to be connected to the nomadic lifestyle of so many of the region’s communities, who may have tended to make only that which they could carry.

Undeterred by the absence of a local tradition of figuration, Trowell, a devout Christian, used examples of religious art from West Africa and medieval European to form the basis of the development of what she claimed to be ‘indigenous’ spiritual sculpture and picture making in East Africa. She otherwise relied on vivid visual descriptions to inspire her students’ work, avoiding at all costs showing them images of contemporary western painting – an important strand of which (Cubism), since the early 1900s, had drawn heavily for its inspiration on sculptural works from West Africa.

What was on the one hand radical – and in a sense, emancipatory – about this move was that Trowell was one of the first colonialists to incorporate indigenous cultural knowledge into colonial education in East Africa. Indigenous knowledge had hitherto been denigrated as primitive and dismissed as pagan by missionaries (who were at this point still solely responsible for the formal education of British colonial subjects). But the genealogy that Trowell constructs nonetheless remains highly problematic: she appropriated the material culture of an entirely different community from another part of the African continent, and claimed it as a universally African, while maintaining the view that engagement with contemporary European art – which is arguably equally remote and/or equally near – would be a damaging act of contamination.

3

The closest period to which she was willing to forge any kind of connection with European culture was with the medieval period – a classical colonialist strategy that reinforced the idea that Africans and their cultures were lower down the evolutionary scale.

4

However well intentioned Trowell’s attempts to ‘develop a modern African Art rooted as far as possible in African tradition’, one might argue, in fact, that in order to create such an ‘African Art’ (with a capital ‘A’) Trowell effectively created an ‘African Other’.

Trowell’s actions appear to be ideologically aligned with the policy of indirect rule that evolved in the British Protectorates under late colonialism. Unlike in the settler colonies (like Kenya and Rhodesia), British rule was exercised indirectly in the Protectorates – devolved to a series of ‘tribally’ organised local authorities who were answerable to British district commissioners in a system of what Mahmood Mamdani characterised as ‘devolved despotism’. Crucially, where there were no local chiefs – that is, where communities had other, less hierarchical forms of social organisation, the British simply created them. ‘Native rule’ was to a considerable extent a British fabrication, that, in the name of supporting indigenous culture, through a form of both spatial and cultural engineering (the logical end point being apartheid), actually furthered the subordination of colonial subjects and made it more difficult for them to mount effective political opposition – denying them power not on racial but on ‘customary’ grounds.

5

Whether by accident or by design, elements of this synthetic discourse of ‘African cultural authenticity’ also feed into the nativist discourses that emerged across Africa in the 20th century, where, lamenting the loss of ‘purity’ that has occurred through the encounter with the West, an argument is widely advanced for a return to a ‘true’ ontological and mythical ‘Africanness’.

It is my contention that the ‘synthetic authenticity’ produced and promoted by these interconnected discourses of art, culture, education and politics continue to have a profound and pervasive influence on both fine art and art education in East Africa. By conducting interviews with both current and former staff and students of the Margaret Trowell School of Art, and by exploring the artworks that they produced, by examining secondary sources in libraries, archives and museums primarily in Uganda, Kenya, the United Kingdom and Germany

6

, and by comparing the establishment of art education and fine art discourse in British East Africa with contemporaneous developments in the Ghanaian and Nigerian Protectorates, I hope to examine the complex and contradictory impulses of emancipation and subordination at work in the development of art and art education in the colonial period, and to consider the long-term consequences for fine art discourse in the region.

1

For the first 20 years at Trowell taught art in British East Africa, she only taught adult male colonial subjects.

2

The Luzira Head is a clay figure which was discovered in 1929 by prisoners excavating at Luzira prison near Kampala. It has been in the collection of the British Museum since 1931.

3 Trowell

managed to maintain this position while also simultaneously introducing painting using oils and acrylics on canvas and board!

4

See Johannes Fabian (1983), Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object , New York: Columbia and Anne McClintock (1995), Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest , London & New York: Routledge.

5

See Mahmood Mamdani (1996), Citizen and Subject: The Legacy of Late Colonialism , Princeton & London: Princeton University Press.

6

The Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt has arguably one of the largest and most important collection of Ugandan art in the world outside Uganda.