About the Africa Cluster (ARAC)

The Africa Cluster of the Another Roadmap School (ARAC) is a group of scholars and practitioners of artistic and cultural education who work in both formal and informal contexts across the African continent. ARAC was founded to foster Africa-based conversations around the arts and education, and in investing in the development of a shared knowledge base and a structure of mutual learning that will benefit African practitioners and contribute to advances in thinking and practice worldwide.

For detailed information about this initiative, take a look at:

ARAC can occasionally be found on

Facebook

and

Instagram

.

– – –

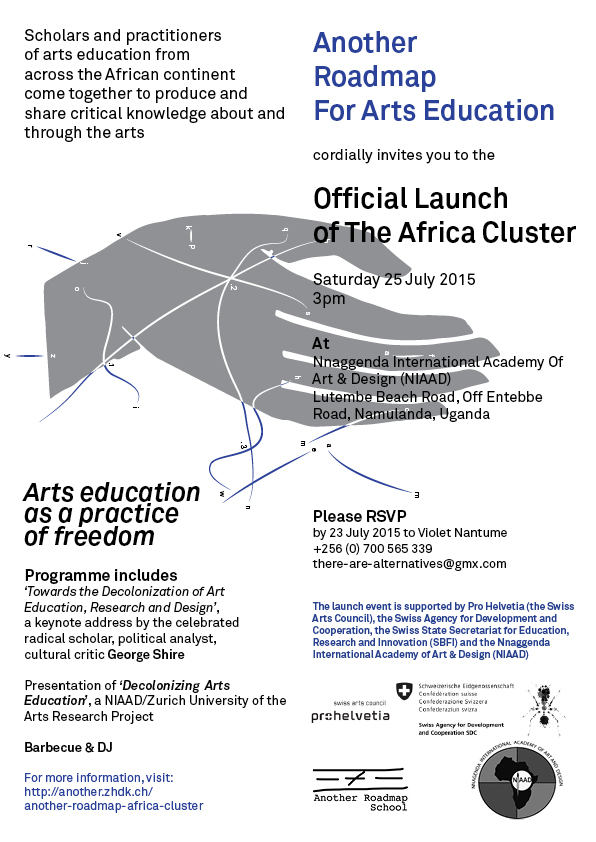

ARAC convened for the first time in July 2015 at the Nagenda International Academy of Art & Design (NIAAD) in Namulanda, Uganda

, where delegates spent four days presenting their work and planning a joint programme of theoretical and practice-based research into artistic education in their respective locales.

The members of ARAC have been collaborating ever since on a programme of research into arts educational practices in Africa. This research is critically informed and grounded in historical analysis, particularly with respect to the continent’s colonial heritage. Funding from ProHelvetia Johannesburg, ArtEDU and the Zurich University of the Arts have enabled the cluster to meet to present their research, to give one another feedback and to strengthen their network at colloquia and meetings in

Sao Paolo (2016)

,

Johannesburg (2017)

,

Maseru (2018)

and

Nyanza (2018)

.

In 2019,

Arts Research Africa invited ARAC to partner with them to organise a symposium on artistic education in Africa

. The symposium took place at various ‘sites of knowledge production and speculation’ in and around Johannesburg, including Trackside Creative, Keleketla! Library, and the Wits School of the Arts, in February 2020.

– – –

ARAC has recently begun to develop a series of publications based on the research they have done over the past five years.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Invited Experts:

George Shire (2015 & 2016), Tracey Murinik (2017), Yuk-Lin Cheng (2018).

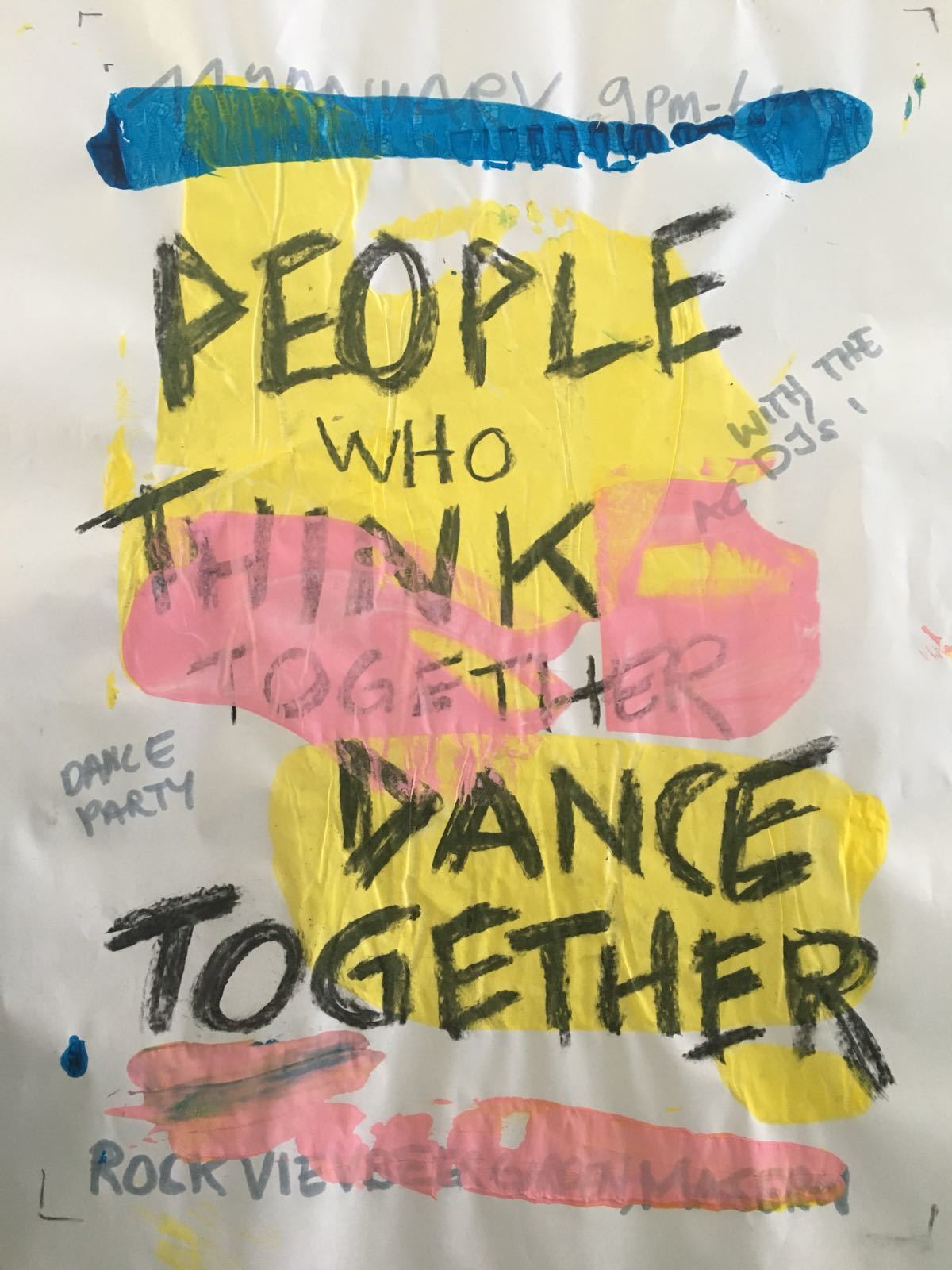

People Who Think Together Dance Together: A Manifesto

In 2018, ARAC was invited by

EDUCULT, an Austrian institute of cultural policy and cultural management, invited ARAC to submit a chapter for the book

Cultural Policy and Arts Education: A first African-European Exchange

(forthcoming).

This

publication was based on the proceedings of

a two-day meeting EDUCULT organised at the Bundesakademie für kulturelle Bildung in Wolfenbüttel (DE)

that was attended by delegates from Kenya, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Germany and Austria.

ARAC were not invited to participate in this meeting,

but its organisers were aware of us and our activities

, and belatedly invited us to share our perspectives on its themes.

For this publication, we submitted a copy of

the interview that Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa gave to START Journal on behalf of ARAC following our inaugural meeting in Namulanda in July 2015

, and we also prepared the following text, which reflects upon how the project developed over the subsequent 3 years.

– – –

What you are looking at here is a poster that was created in an impromptu silkscreen workshop that took place during the third colloquium of the Africa Cluster of the Another Roadmap School in Maseru, Lesotho in January 2018. The poster was made using a prototype for a ‘Silkscreen-in-a-Box’ kit that was designed and built by our Johannesburg Working Group.

For the past two years, our colleagues in Johannesburg have been investigating the work of the Medu Art Ensemble, which was formed in 1977 by a group of cultural workers who had fled apartheid South Africa for Botswana. Medu’s members, who self-identified as cultural workers rather than artists, used a diverse range of forms and media to create awareness of the struggle against apartheid and to sustain and to amplify that struggle. In 1984 the Medu Art Ensemble begun to develop a ‘Silkscreen-in-a-Box’ kit that could be smuggled into South Africa and used by anti-apartheid activists in the townships who had little or no training in printmaking. Unfortunately the kit never got beyond the prototype phase because in 1985 the South African Defence Force raided Medu’s offices in Gaborone, killing 12 of its members and bringing the Medu Art Ensemble’s activities to an end.

The

Another Roadmap School – Africa Cluster argues that the story of the Medu Art Ensemble is a vital and significant example of what culture production and cultural mediation have achieved in Africa in recent history. It is one of many important case studies that we seek to recover in our work and to reactivate in art education in the present.

– – –

The second thing to mention about this poster is its main text or title:

People who think together dance together

. This statement emerged somewhat casually as the title of an event organised by an Africa Cluster member who had insisted from the outset that the programme for our colloquia had to include a dance party. Our colloquium, so their argument went, could not just comprise presentations of research, feedback sessions and and sessions to plan how we could take what we were learning back to our communities and constituencies. As an integral part of this work, this person maintained, we also had to dance together. Over time the statement –

People who think together dance together

– has acquired a meaning and a value that we did not initially foresee: we have come to recognise it as a concise indication of the potential inherent in radical and emancipatory approaches to culture, education and knowledge in post-independence Africa.To give you an example: our survey has been neither exhaustive nor scientific, but we are, as a group, yet to find an indigenous African language possessing words that translate directly to the English words ‘art’ and ‘design’. Anytime that these words are required, we observe people in Africa to use their European equivalents. Now, this obviously does not mean that indigenous Africans are not creative, that they are not producing and exchanging symbolic meanings. It just means that in most indigenous African cultures, such practices have a very different social, cultural and economic distribution.

It also means that if we are to genuinely understand and to meaningfully engage with cultural production and cultural mediation in Africa today, the use and validity of European terms such as ‘art’ and ‘design’ have to be problematised. Our colonial inheritance of separating of certain practices and bodies of knowledge into ‘disciplines’ must be dissected and then set aside. As the Africa Cluster, we have come to believe that it is the only way, epistemically, that we will ever be able to start to understand and appreciate African cultural production over the long durée, and to create just and sophisticated accounts of how cultural and knowledge-producing practices on this continent have evolved, endured, and indeed continue to drive the discourses of the present.

One consequence of this is that we as the Africa Cluster take

‘symbolic creative work’ – a term we prefer over ‘the arts’

– extremely seriously as a form of knowledge production. And by this we do not mean that each such a work encapsulates and encodes a concisely formulated message – rather, that making, doing and participating in such work is a form of knowledge production –

a way of

doing the thinking

. And very often it is also a way of doing the thinking

collectively

. So even though the sentence

People who think together dance together

might sound quite light, it is now effectively part of the Africa Cluster’s manifesto, and an entry point into a set of ideas that, in our contexts, we believe need urgently to be addressed.

Over the past three years we have only just begun to interrogate this epistemological territory, which has been formed by the political and social upheavals that the peoples of the African continent have undergone, particularly since the mid-19th century. Mapping and excavating this territory has the potential, we believe, to create new spaces for the consideration and appreciation of cultural practices that elude the framework of

Eurocentric cultural vocabularies and thus contribute to important shifts in pedagogical practices, and in forms of social and cultural organisation.

– – –

Thirty years after structural adjustment wreaked havoc on the continents’ economies, neoliberal capital’s grip on formal education in Africa is decidedly firm. Against a background of rising authoritarianism and crippling cuts in what was only ever modest public funding, the commodification and marketisation of education is leading to the erosion of spaces of critical thought and practice, and concerted attempts to erase ‘the possibility of thinking otherwise’. (1) For the school and university employees among us who are committed to arts education’s capacity for the production and accessing of critical knowledges, this represents a crisis.

There can hardly be a more poorly resourced academic discipline than arts education in Africa today. There are very few departments of art education, there are almost no professorships, there are virtually no research institutes, and there are very few publications.(2) NGOs – most notably western NGOs with so-called ‘development’ mandates, also western universities – have stepped in to offer workshops and short courses to aspiring artists in both the formal and informal sectors. However, although well meant, these efforts are all too often poorly conceived, ill-informed, lacking in criticality and devoid of local accountability. There are – and will always be – vibrant and vital grassroots initiatives, but they tend to operate under conditions of extreme precarity, reliant on the vagaries of project funding and thus forced to devote far too extensive time and energy to filling out forms and accounting to funders. This means that such initiatives are unable to focus their energies on documenting and systematising the knowledges that they produce, on building their institutions, on strengthening their networks and on publicising their insights and achievements. Because therefore, of this widespread lack of research and documentation in arts education in Africa, important theoretical and practical innovations frequently go unrecorded and unrecognised beyond their immediate locality, and far too little valuable knowledge is disseminated in the present or archived for the future.

As a result, as art education has evolved into a global discourse over the past two decades, Africa has remained one of the regions least likely to see its concepts of ‘art’ and ‘art education’ reflected in supranational policy documents such as

UNESCO’s

Road Map for Art Education

(2006)

. And yet, because of the chronic lack of investment in arts education at a continental level, this is the region whose educational and cultural policies are often most reliant upon documents of this kind. Consequently Africa is one of the regions most vulnerable to these so-called ‘universal’ documents’ deficiencies and abuses.

A chronic shortage of good quality, affordable and locally accessible resource materials means that the curricula for arts education in Africa’s schools and universities remains overwhelmingly Eurocentric. Not only can this result in teaching of profoundly questionable relevance to students, but it can also instil and reinforce corrosive and unwarranted feelings of cultural inferiority.

One of the reasons for convening the Africa Cluster was a shared belief that Africa’s students, teachers and policy makers should no longer have to rely on research and on concepts that have little or no relevance or connection to their local contexts. We came together to address this need, and to try to fill in some of the gaps.

It is a formidable task, and we are, after all, a small group of people with extremely limited time and money. But in the past three years, we have made inroads. The funding we have received from ProHelvetia Johannesburg, from the Mercator Foundation Switzerland and the Allianz Foundation have enabled us to carve out pockets of time to undertake some of this vital work with our students and with our peers. And what has catalysed and sustained these efforts is that this project has enabled us to meet – something that, for economic reasons, it is almost impossible for art educators within Africa to do. By coming together regularly to talk about what we teach, how we teach, how we learn, what we think learning is and what we think knowledge might be, we are slowly building a base of Africa-specific knowledge and identifying extraordinary and unexpected connections between our respective contexts. In addition to producing and sharing knowledge, the Africa Cluster is thus enabling us to pool resources and to develop alliances that are enabling us significantly to expand the arts educational possibilities in our locales both inside and outside the academy.

The Africa Cluster has been an extraordinary gift and an extraordinary journey from which we are all learning, and from which, as a result, those that we teach are learning too. We greatly hope that we shall be able to secure the support we need to continue and to amplify our efforts in the years to come.

– – –

Footnotes

(1)

Sara Motta, ‘Pedagogies of Possibility: In, against and beyond the Imperial Patriarchal Subjectivities of Higher Education’ in Stephen Cowden & Gurnam Singh (eds)

Acts of Knowing: Critical Pedagogy In, Against and Beyond the University

, London: Bloomsbury Academic Publishing, 2013, p. 90.

(2)

We have so far identified one journal special issue published in recent years (

Critical Interventions: Journal of African Art History and Visual Culture

, Special Issue on Arts Education in Africa,

8:1, 2014) and one analysis of the history of art education in Morocco (Hamid Irbouh,

Art in the Service of Colonialism: French Art Education in Morocco 1912-1956

, 2013).

Artists and Art Education in Africa,

a volume based on the proceedings of a symposium that took place in London in 1995, is still being prepared for publication more than 20 years after the symposium took place. Doctoral theses such as Firoze H.Somjee Rajan’s ‘Learning to be indigenous or being taught to be Kenyan: The ethnography of teaching art and material culture in Kenya’ (1996), Rhoda Elgar’s ‘Creativity, Community and Selfhood: Psychosocial Intervention and Making Art in Cape Town’ (2005) and Attwell Mamvuto’s’ Visual Expression Among Contemporary Artists: Implications For Art Education’ (2013) remain unpublished. One notable recent exception is Nicole Lauré Al-Samarai’s 2014 study,

Creating Spaces: Non-formal Art/s Education and Vocational Training for Artists in Africa between Cultural Policies and Cultural Funding

, which was a study commissioned by the Goethe Institut Johannesburg. (Free to download in English, French and German from:

https://medienarchiv.zhdk.ch/entries/85cea527-dde4-437b-befe-b511a833d20e

)

Another Roadmap Africa Cluster to impact art education on the continent: Q and A with Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa. (16 September 2015)

Following the inaugural meeting of the Another Roadmap Africa Cluster in Uganda in 2015, Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, who organised the meeting, sat down for an interview with Dominic Muwanguzi for

START Journal – Magazine for Contemporary Arts and Culture in East Africa.

The interview is reproduced here with the kind permission of the START JOURNAL editorial board.

In July 2015 you were at the Nagenda International Academy of Art & Design (NIAAD) in Namulanda to launch the Another Roadmap Africa Cluster.

What is this project about?

The Another Roadmap Africa Cluster are a group of scholars and practitioners of artistic and cultural education, working across the African continent, who have come together to pursue a joint programme of research into arts educational practice in Africa that is critically informed and grounded in historical analysis. The group’s aim is to produce and to share knowledge about and through artistic and cultural education in Africa, and to make this knowledge available both across the continent and worldwide.

The Another Roadmap Africa Cluster will pursue a joint programme of research into arts education in Africa, focusing on 4 key areas:

-

Policy

: The analysis of policies and practices of arts education currently influential within various African contexts; -

Art Education Histories

: The assessment of the continuing hegemony of colonial westernized arts education in Africa; -

Other Roadmaps

: The plotting of alternatives and the development of other paradigms for practice and research in artistic education in Africa. -

Knowledge Transfer

: The research and development of strategies for making useful knowledges accessible and usable in our local contexts.

With this programme, the Another Roadmap Africa Cluster aims to make a lasting impact on arts education in Africa by creating a vibrant forum for exchange between Africa’s cultural scholars and practitioners and by producing research that is specifically targeted at Africa-based practitioners and policy makers.

The idea to decolonize art education seems to me to be overly ambitious, especially in Uganda where one of the local languages, Luganda, was used as a tool of colonialism. Don’t you think this is a futile agenda?

I agree that it is ambitious to attempt to decolonize artistic education. But the scale of the challenge does not mean that it is not worth the attempt. Far from it: colonial power relations, and, in particular, the subordinate mentality that it, as a system, sought to instil in Africans, continues to impact decisively on relations of power, and on concepts of knowledge and value in ways that are perilously and generationally debilitating for far too many people on this continent.

A clear example of this is the extent to which European languages (admittedly for a complex range of reasons) continue to be widely used as what I once heard the Ghanaian academic Ato Quayson call the ‘languages of power’ in post-independence Africa. Indigenous African languages are regularly marginalized in law, in government, in journalism and in the education system within the very regions in which they originate. They are too rarely taken seriously by those with power as tools for serious discussion and debate. So-called “intelligent”people converse in the languages of former colonizers.

Immigrants settling in Africa from Europe and North America and their descendants can prosper here for generations without ever needing to acquire a proficient grasp of the languages of the people among whom they live. The obverse is decidedly untrue. In fact, it can get worse: last year I met the chairman of an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp on a beach on the shores of Lake Victoria, south of Mukono. He and his fellow fishermen were unfairly evicted from their homes on the islands in the lake ten years ago, and they have been fighting for redress ever since. When we met, the chairman of the camp expressed to me his belief that one of the main reasons that he has struggled to get anyone in the Ugandan government to pay serious attention to the plight of his community is because he cannot speak or write English. If this is true, then in this respect, this man is the victim of the colonial mentality of certain contemporary Ugandans.

The use of European languages might make the work and ideas of Africans more readily accessible to some foreigners, but it also limits the participation in discussion and decision-making of people who have not had access to formal European-style education. And ideas of such people should never automatically be dismissed as ignorant or irrelevant. People who don’t speak European languages, people who have had no formal European-style education also produce and preserve important and useful knowledges. Often indigenous knowledges. The dominance of European languages within African discourses can therefore restrict the access to and circulation of rich and valuable ideas, imaginaries, philosophies and world views.

So it’s a slow and difficult task, but part of what the Cameroonian theorist Achille Mbembe describes as ‘the difficult work of freedom’ in postcolonial Africa is, as I see it, to de-centre western cultures, western languages and western epistemologies, and to clear a space in which their indigenous counterparts can be reconstituted as centres of gravity.

And just because a particular indigenous culture or language group was implicated in colonial rule does not necessarily mean that that language or culture can play no role in emancipation. Some Baganda may have been complicit in British colonialism, but many others fought vehemently against it: Dr Kizito Maria Kasule, the founder of the Nagenda International Academy of Art & Design (NIAAD), which hosted the first meeting of the Another Roadmap School – Africa Cluster, is a Muganda from Masaka. The British sentenced his father to 5 years’ hard labour in the 1940s for his role in anti-colonial struggles in the Uganda Protectorate, an experience from which he never fully recovered.

A project like this obviously encounters many challenges. What are some of those challenges you have already faced?

The Another Roadmap Africa Cluster has only very recently been constituted. We have faced relatively few challenges to date: so far, all of the institutions and individuals we have invited to participate have agreed to take part; we were able to raise just enough money to hold our first face-to-face meeting; a good sized audience of Uganda-based artists, arts practitioners and academics attended the launch event at NIAAD on 25 July. For the most part, our efforts and our ideas have been well received by scholars, practitioners, policy makers and funders with whom we have met. But we have not been lulled into a false sense of security. Far from it. The truth is that the real, the difficult work is still ahead of us – that is, doing the research, doing it well, and then persuading our peers of its value.

The conversation among many art elites on the continent today is about Pan African ideology in the arts. This can be seen with many workshops and exhibitions staged on the continent like the Art at Work Workshop, Artwork project, Dakar Biennale, the forthcoming Bamako Encounters and Kampala Art Biennale. Is this project part of the debate?

It largely depends on what you mean by ‘Pan-African ideology’. I personally understand and attempt to practice Pan-Africanism (more or less following Kwame Nkrumah), as an ideological and activist commitment to the solidarity of people of African origin both on the continent and in the diaspora, and to the idea that the unity of people of African origin is essential for Africa’s long-term economic, social, political and cultural progress.

I simply don’t know enough about the initiatives that you reference to be able to speak with any confidence about their Pan-African ‘credentials’. But it’s worth pointing out that just because an event brings Africans together does not necessarily make it Pan-African – strictly speaking. At the same time, and in this day and age, any such initiative nevertheless possesses that radical, emancipatory potential: one of the most serious colonial continuities to afflict post-independence Africa is that so many factors – often external factors – conspire to continue to make it difficult for Africans to meet, to exchange and to join forces. One simple example: it took longer and cost more money for Ayo Adewunmi to fly from Nigeria to Uganda to attend the first meeting of the Another Roadmap Africa Cluster in July on behalf of the Lagos Working Group than it would have taken him to fly to Europe. To me that is plain wrong.

It also depends on what you mean by ‘art elite’. I consider that to be a contentious and problematic term, particularly in the African context, where opportunities and resources are so unevenly distributed. There is a growing discontentment, about which your readers are no doubt aware, for example, regarding the extent to which influential global discourses on African art and the attendant opportunities for economic and social advancement tend to be dominated by artists and curators in the diaspora, who enjoy increased mobility, resources and greater access to wealthy western consumers and funders. I am well aware I could be said to fall into this category.

My individual identity/ status notwithstanding, I believe the Another Roadmap Africa Cluster to be borne of a commitment to the principles of Pan-Africanism that led to the foundation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) back in 1963. Like the OAU, its aims are also anti-elitist. The Another Roadmap Africa Cluster is a grassroots initiative that aims to support, develop and promote the work of Africa-based scholars and practitioners of artistic education from the bottom up. Although we ultimately hope to make a positive contribution at governmental and supranational policy level, we have no interest in being elitist per se.

You are intensively involved in research. What have you been able to discover when it comes to the influence of western art education on art graduates on the continent today?

My own research into artistic education in Africa is still very much in its infancy and my knowledge is far from extensive. So at this point I can sadly only speak in crude generalizations. But what I do know is that the impact of western art education in Africa varies enormously according to the context.

It is extremely important to remember that ‘art’ and ‘education’ are neither self-evident nor universal concepts. Many aspects of the ‘symbolic creative work’ that is and has historically been practiced and transmitted within African societies does not fit neatly into western definitions of ‘art’, ‘education’ or ‘art education’. In many instances, under colonialism, such practices, where they were visible to colonisers, were devalued and systematically suppressed, often on the grounds of their supposed paganism or ‘impurity’. But some of these practices ‘flew under the radar’, so to speak, and have continued to flourish, largely free of the external imposition of western ideas. Other forms of indigenous symbolic creative work were, for complex and sometimes problematic reasons, positively endorsed and encouraged by colonisers. (This was often the case with music and dance in many African societies.). And still others, as is the case with figurative painting and sculpture in Uganda, were introduced into African societies by the colonisers themselves. And in many respects, those societies have, over time, made those imported art forms their own.

My current research focus is visual arts education in the Uganda Protectorate and in the subsequent republic. I am not in a position to speak with any authority about the influence of western art education on the teaching of music, dance, literature or drama, for example, anywhere on the continent – or, indeed, anywhere in the world. But what I have observed within visual arts education in Uganda/the Uganda Protectorate so far is that western models remain extremely dominant within formal education. When they were founded, most art schools in Anglophone Africa began by basing their curricula on those of pre-existing European and North American art academies, and this has not changed much in the post independence era – certainly not in Uganda.

I have also observed the western models that the major Ugandan art schools tend to follow are often highly fragmented, and frequently rather outdated. Conceptual art, multimedia and performance, for example, which have been well established features of western art schools curricula since the 1970s – and which, incidentally, have far, far deeper roots in East African cultures than figurative painting and sculpture – feature minimally in current formal Ugandan art curricula. African art histories continue to be marginalised within the teaching of art history, which remains largely Eurocentric, and consequently, to my mind, therefore, of questionable local relevance. In the informal sector, however, things tend to be quite different. But the informal sector is also much less likely to be influential on a policy level, and often has more fragile institutional infrastructure.

There is talk in some circles within the local art scene about opening up an art museum. What impact does such infrastructure have on art education and the overall growth of the art industry?

This is a complex question. The impact of museological infrastructure varies so much according to the context – on both historical and contemporary conditions.

In the case of Uganda, one of the ‘fractures’ or ‘disconnects’ that I observe in its dominant models of formal visual arts education is that, for historical reasons, its pedagogies construct concepts of value, and produce narratives about art and the artist’s trajectory are oriented by the idea of the museum. The museum serves as the arbiter of quality and legitimacy. The problem with this approach is that there is no art museum in Uganda, and very few art students ever have access to one during the course of their studies. So their education trains them to orient themselves and their work in relation to something that is largely abstract and wholly remote. To my mind, this does not make sense.

While I fully appreciate Ugandan artists’ desire to have a place to go locally to see art ‘properly’, it’s is not necessarily a problem, in my opinion, that there is no dedicated art museum in Uganda. Not only are museums notoriously expensive to maintain (and I am not persuaded that there is currently either the capital or the political will in this country for such a steep and open-ended investment), but the existence of the building is not in and of itself the solution. All over the world, museums are frequently empty and under-utilised: just because the place is there does not mean that people will use it. At the end of the day, it is good programming that will draw in an audience, and you don’t actually need a museum to run a rich and vibrant visual arts programme. In fact, in many cases, a building is a hindrance rather than a help.

I also question the appropriateness of the museum as form in Uganda. As institutions, museums evolved, in the western context, to place art at a remove from everyday life, framed by the aesthetic choices of social elites. This runs counter to what I know of the histories of cultural practice in this part of East Africa, where art has, for generations, been far more fully integrated into people’s everyday lives. To place art in a museum in Uganda would be to attempt to rarify it, and this would run counter to an aspect of local culture and tradition that I personally think is worth preserving and developing.

From my perspective it would be more helpful to focus on programming than on building. What would make the biggest difference to the quality of formal visual arts education in Uganda would be to devote more energies to fostering a local culture of exhibition-making (and exhibition-going), to create more vibrant, accessible and yet rigorous spaces where art can be discussed, critiqued and explored, and to place such activities at the heart of the visual arts curriculum.

While I am skeptical regarding the merits of establishing an art museum in Uganda, I do think there is one of a museum’s traditional activities that urgently needs to be invested in and institutionalised here, namely the collection and conservation of art works. Too few of the best examples of Ugandan art are held in local collections, too little of the work that is here is readily accessible to students and lecturers (hence the need for more exhibitions), and the conservation of that work can sometimes leave something to be desired. The tremendous efforts that the team at the Makerere University Art Gallery have made over the past few years to improve the conservation and documentation of its collection is very important in this respect. It shows how much can be achieved with determination, care and modest means. There need to be more initiatives like this, and we should work to create more opportunities for that and other Ugandan art collections to be seen, researched, debated and written about.

Another Roadmap Cluster to impact on art education on the continent- Q&A with Wolukau-Wanambwa

0

no comments yet

•

No one following this article yet.

•

265 views